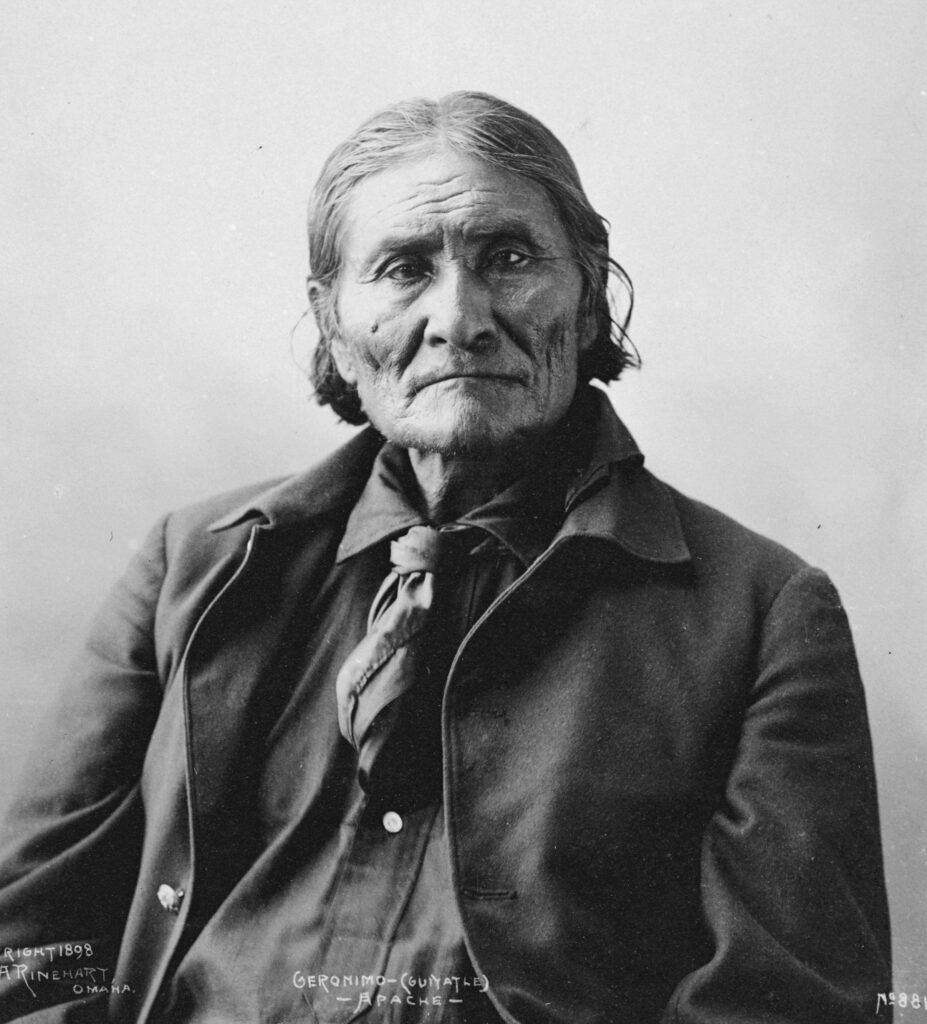

Mysterious Shadow Figure in Old West Photo

Who or what is the mysterious shadow figure in the background of this old west photo? Glance at this 1886 image of Geronimo’s surrender and you might miss the strange form behind the Apaches. But look closer and you’ll spot it: a dark figure rising over the fourth Apache from the right, behind the frame of the wickiup. Can you solve this historical mystery?

The photo was taken during negotiations between Geronimo and the U.S. cavalry for the old shaman’s surrender in 1886. C. S. Fly, a famous Tombstone, Arizona photographer, captured the striking image. It shows the kidnapped boy Santiago “Jimmy” McKin standing in front of Apache children and warriors. It’s one of the most powerful images of the old west ever taken.

Geronimo’s band of Apaches kidnapped eleven-year-old Santiago McKin on September 11, 1885. In a valley east of the Mimbres Mountains in southwest New Mexico, Santiago and his 17-year-old brother Martin were herding cattle. Their father had gone to Las Cruces for supplies. During the boys’ noon break, Martin sat reading a book under a tree while his younger brother played in the creek.

The crack of a rifle-shot broke the noon stillness. Santiago looked toward his brother and saw an Apache he’d later identify as Geronimo run up to Martin and strike his head with a rock. Martin’s head was crushed. When Santiago tried to run, the other Apaches caught him. Geronimo removed Martin’s coat and shirt and put them on. He questioned Santiago in Spanish. How many horses, how many men. Santiago gazed up into the old shaman’s hypnotic eyes. The boy couldn’t speak.

The Apaches put him on the back of a horse and they rode out.

Geronimo was 63-years-old and the days of his desperate, brutal fight were coming to a close. His raid down the valley and the kidnapping of the McKin boy would set the borderland on alert. Cavalry troops patrolled the international line. Geronimo succeeded in leading the escaped Apaches across the border into Mexico, but Geronimo had escaped the reservation for a fourth and final time and now his run would soon be over.

Mexico City cooperated with Washington DC. 5,000 U.S. Cavalry troopers chased Geronimo’s small band deep into Mexico, guided by Apache scouts. Without the scouts, it would’ve been an almost impossible task.

Santiago lived on the run with the Apaches as they raided Mexican ranches. Months passed. Fall turned to winter. Already he’d lost much of his old language, immersed in Apache culture. His captors worked closely on the boy, teaching him their ways in a brutal process of initiation, stripping him of his old identity. Stockholm syndrome set in—the development of a psychological bond between captive and kidnapper.

By January 1886, Geronimo and the weary, out-numbered Apaches agreed to discuss surrender with General Cook. The meeting took place on March 25 at Canyon de los Embudos. Capt. John Bourke wrote of seeing a group of young boys in the Apache camp, and “one of them seemed to be of Irish and Mexican descent.” Bourke wrote, “After a little persuasion, he told… that his name was Santiago Mackin (sic) and he had been kidnapped in Mimbres, New Mexico…” Traveling with General Crook was C.S. Fly, a true pioneer of old west photography. The next morning, Fly received permission from Geronimo to take photographs.

When the Apaches tried to give the boy up to the cavalry, he acted like “a wild animal in a trap” and would speak only Apache. Finally in April 1886, Santiago boarded a train with his former captors, who were bound for prison in Florida. The train stopped in Deming, New Mexico, where Santiago’s parents John and Luceria picked up the boy, who wore only a breechclout. The McKinns took him to the mercantile and dressed him in new clothes before carrying him home at last. Santiago McKinn grew up to marry a woman named Victoria Villanueva and fathered four children. He passed away in Phoenix, Arizona, on December 10th, 1941, at the age of 66, three days after the attack on Pearl Harbor.

The photograph of Santiago McKinn was famously used in the end credits of the Paul Newman movie Hombre in 1967, based on the great Elmore Leonard western. Until recently the shadow figure in the background went unnoticed, then a colorized version was featured on the cover of my historical novel Far Blue Mountains, and curious readers contacted me about the spooky photobomber. Far Blue Mountains is the astonishing story of the last free Apaches, who lived in hiding in the Sierra Madre well into the 1930s. My novel makes use of the 1886 photo, but my story was inspired by the true events of the Fimbres Apache conflict of the 1920s—an injured Apache girl adopted by a powerful rancher, the rancher’s son kidnapped by the last free Apaches. It might sound like something out of Ripley’s Believe it or Not, but the Apache kidnapping that inspired my novel took place it 1926.

Tell me your explanation for the mysterious shadow figure in the photo! Solutions to the mystery range from a hide covering draped over the wickiup to more supernatural possibilities. Those inclined toward the supernatural have speculated that the figure might be one of the legendary Mountain Spirits of Apache mythology. As part of their religious ceremonies, Apache dancers wear crowned masks to portray the supernatural entities known as Mountain Spirits. Pictured above are several Apache crown dancers in a historic photo by Edward Curtis, featured on the cover of Deathsong, the second book of my Beloved Captive trilogy of historical novels.

Max McNabb is a writer from Lubbock, Texas, and the editor of TexasHillCountry.com. He grew up on the family farm outside of Ropesville, Texas. Though Norm Macdonald once called Max a “lonesome drifter,” he still lives in West Texas. He is the author of the Beloved Captive Trilogy of historical novels: Far Blue Mountains, Deathsong, and Sky Burial.